Cholesterol: The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly!

It seems like there are so many conflicting theories surrounding cholesterol out there on the internet: “fat is the root of all evil and causes strokes and heart attacks”, “fat is good for you”, “eggs are bad for you”, “butter in your coffee makes you bullet proof”, etc. So, when your cholesterol comes back elevated, what should you do?

In 2020, The Journal of the American College of Cardiology published an article calling for a reassessment and proposal for food-based recommendations surrounding cholesterol. It specifically looked at saturated fats, which the guidelines have recommended limiting to 10% of your diet since the 1980’s. The problem with the guidelines is that they make a blanket statement that recommends limiting ALL saturated fats, but not all saturated fats are created equal.

To start, the term saturated fat typically refers to foods that are mostly made of saturated fatty acids that are solid at room temperature (think butter, lard, etc.). However, saturated fats are made of more than one type of fatty acid and can have more than just saturated fatty acids in them. Then there is the term saturated fatty acid or SFA. This refers to specific chemical structure of one type of fat. There are 4 types of SFAs: short-chain, medium-chain, long-chain, and very long-chain. The length of the chain is based on the number of carbon atoms (short-chains have 4-6 and very long-chains have 22). Different foods have more of some chain types than others. For example, dairy fats (a saturated fat) are a major source of short-chain SFAs and red meats have more long-chain SFAs. This doesn’t mean that dairy fats only have short chain saturated fats, but rather that different food sources have different proportions of each of the types. SFAs are also classified by the number of methyl branches they contain. You’ve probably heard of branched-chain fatty acids – that means that the SFA has at least one methyl branch coming off its chain. Branched-chain SFAs are found in dairy and beef. There are multiple other types of classification systems, but those two (chain length and # of methyl branches) are the big two.

Since the 1950’s, research has focused on the harmful effects of dietary fat on heart health and the US dietary guidelines have recommended 10% of a person’s intake come from saturated fats. This has often led to the replacement of those calories with carbohydrates. However, much of the data was from smaller, less rigorous studies done 50+ years ago and more recent studies from across the world have shown no association between saturated fat consumption and cardiovascular risk or risk of death. In fact, in one of the largest and most diverse studies (PURE), it was found that a diet higher in carbohydrate was associated with higher risk of death and the individuals with about 14% of total daily calories from saturated fat had a lower risk of stroke! This was supported by the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial that followed 49,000 women and showed that the risk of stroke and heart attack were the same even after 8 years on a low-fat diet.

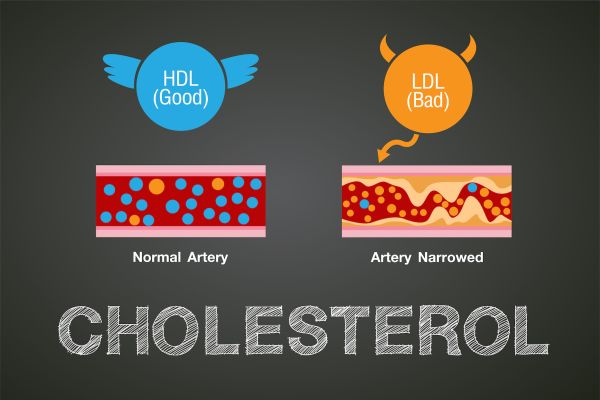

So, does that mean I get to eat bacon?.. Not so fast! First, find out if you’re really at higher risk. Most doctors routinely test patients’ cholesterol panels every year. We look at the total cholesterol, but also the good (HDL) and bad (LDL) cholesterol. Traditionally, if your total cholesterol and bad cholesterol (LDL) are too high, you were deemed at higher risk of stroke and heart attack. However, we learned that good cholesterol (HDL) can be protective and artificially make the total cholesterol look “too high”. Therefore, many physicians then turned to the LDL (bad cholesterol) as the primary indicator of whether someone was at risk. If a patient has an LDL (bad cholesterol) over 100, they were deemed at high risk and previously were instructed to reduce their saturated fat intake.

However, we have now learned that all LDL is not created equal and there are different kinds of LDL subtypes – mainly large LDL particles and small LDL particles. Large LDLs have more cholesterol, but actually have lower risk associated for cardiovascular disease (stroke and heart attacks). Small LDL particles have higher risk for disease. Most recently, a new type of marker is being used to further stratify patients’ risk of stroke and heart attack called apolipoprotein testing. Apolipoproteins are proteins that bind fat. Apolipoprotein A is found in HDL (good cholesterol) particles and Apolipoprotein B is found in LDL and Very Low Density Lipoprotein (VLDL). In people with high LDL, a new way to better understand their risk is to check the ratio of ApoB/Apo A. A higher ratio indicates a higher risk of strokes and heart attack.

So, what do we do if our risk is high? Should I reduce my saturated fat intake? Yes and no! Significant research is now being done on what we call the “food matrix” – the various components of the food including saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and other molecules. We now recognize that other food components play an important role in how SFAs behave in the body. Cheese and yogurt are a major contributor of saturated fat in many diets across the world and consist of multiple kinds of SFAs, proteins (casein and whey) and vitamins and minerals as well as probiotics. Multiple studies have shown higher levels of dairy intake to lower the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death despite the high content of SFAs. This is thought to be related to its complex food matrix and the effect of other molecules within dairy products.

The biggest question surrounds dietary meat consumption. Undoubtably, studies show that processed meats increase the risk of heart attack and stroke and diabetes. Processed meats are meats which have been salted, smoked, cured, canned or had chemical preservatives added to them. Examples include deli lunch meats, spam, sausages, hot dogs, salami, bacon, jerky, corned beef and smoked meats. However, there is little evidence that unprocessed meat and poultry in small amounts (1 serving per day) increase the risk of death or cardiovascular events (strokes and heart attacks). Therefore, the current recommendations are to avoid processed meats, but that it’s likely safe to have small amounts of unprocessed meat and poultry in your diet.

Finally, consider the overall composition of your diet (i.e. what percent comes from carbohydrates vs. fats vs. protein). In a study with almost 200,000 participants from the UK, the people with the lowest risk of death were those with diets that were the highest in fiber (10-30g per day) and protein (14-30%), and relatively low in carbohydrates (20-30%). Based on the high fiber content, most of their carbohydrates likely came from fruits and vegetables. In addition, a large portion of their daily fat intake came from unsaturated fats which are found in eggs, nuts, plants, and seeds. Unprocessed, whole foods are generally much healthier and safer for you and in a balanced diet with reasonable sized portions should actually be beneficial for your health and your cholesterol!